During the 1993 Mississippi River flooding, while watching the national nightly news with my mother, a reporter stuck a microphone into the face of a resident whose family home was quite literally floating away, asking “What will you do now?” The stoic response was something to the effect of “Well, guess we’ll just start over.”

“That’s America,” said Mom.

An émigré from Cuba born just after the family lost 3 young children and their home in a in a 1932 hurricane, forcing a relocation to another city to live with relatives, my mother saw this response as emblematic of the United States and its people, a place where most anything is possible and the resolve to begin anew and carry on is deeply engrained.

Starting over after being displaced from somewhere is – after all – a very American story. In the context of engaging communities facing the impending effects of climate change – especially coastal and riverine communities – the option of retreat, however, is often a nonstarter.

When did ‘retreat’ come to equate to ‘surrender’?

Its implications – primarily from military history – are fairly clear. However, there is distinction between retreat and surrender. Remember, WWII’s Dunkirk evacuation – Operation Dynamo – was a retreat. But we all know that the Allies won in the end.

So why does ‘retreat’ stick in the craw?

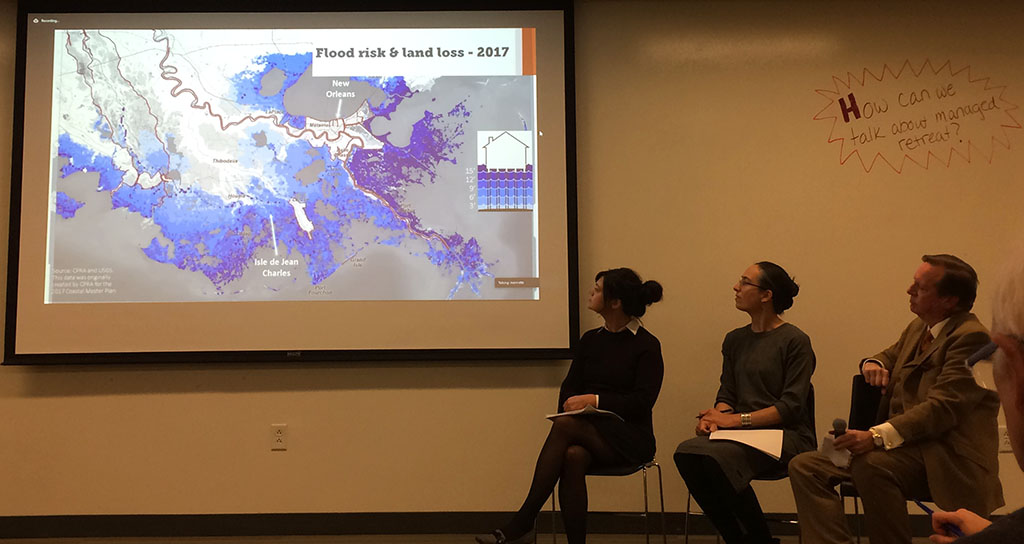

This was the subject of “Designing Boston: Can We Talk About Climate Migration?” part of series of conversations presented by the Boston Society of Architects on October 23, 2018. Moderator Armando Carbonell of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy shepherded a lively discussion with panelists Ona Ferguson, Senior Mediator, The Consensus Building Institute (CBI); Darci Schofield, Senior Environmental Planner, Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC); and Jeanette Dubinin, Director of Coastal Program, Center for Planning Excellence (presenting remotely).

Should We Stay or Should We Go?

Ona Ferguson touched on CBI’s work with the towns of Kingston, NY and Piermont, NY – both situated along the Hudson River, and which have experienced periodic downtown flooding and Hurricane Sandy flooding, respectively.

CBI helped facilitate small-group community dialogues on future risks, finding synergies between local and state coastal resilience plans, and – most importantly – on being able to approach managed retreat as a viable option.

A result is the website climigration.org, a place for sharing solutions, case studies, and more, which gets a tip of the hat for bringing subtle humor to a subject too often addressed in hushed tones: the website bears a subtitle from a song by The Clash – Should We Stay or Should We Go?

Jeanette Dubinin spoke of her organization’s work with Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana, one of the most vulnerable and quickly-disappearing communities in the United States, dubbed ‘America’s first climate refugees‘ by the New York Times in 2017 (the intent is appreciated, but there are earlier historical examples, and we ain’t talking just prehistoric times).

The bayou region’s mix of Acadians from Nova Scotia fleeing British rule in the 18th century and Native Americans – many fleeing the U.S. government’s pursuit to dislodge the Seminole and other from Florida – as well as local native peoples have been further marginalized by the Gulf Coast petroleum industry’s shaping of the land. Access canals were cut which sped coastal erosion, contributing to turning a healthy wetland ecosystem into an island in 60 years.

Elizabeth Rush writes of Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana in her lyrical 2018 book ‘Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore’:

Living in this marshland – considered uninhabitable by most mainland Europeans – was a kind of shared survival tactic, and Acadians and Native Americans thrived together here. But today the high rate of intermarriage between these groups means that the federal government does not recognize the residents as Natives. And since the island was never formally a reservation, there is no federal mandate to relocate the islanders now that their home is disappearing.

Harvard Center on the Environment researcher A.R. Siders points out that this community originally settled in a vulnerable area precisely because of historic discrimination. While connections to the environment are deep and poignant (again, read Rush’s conversations with Isle de Jean Charles residents), is this pattern being perpetuated by moving them again?

However, things are moving, to a large degree with residents themselves in the lead in planning scenarios where managed retreat / relocation – to towns such as Houma to the northwest – are front-and-center. Dubinin and the Center for Planning Excellence’s engagement with the population – facilitated by $48 million in HUD / Rockefeller Foundation funds from a successful entry to the National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC) – has included a similar engagement process to CBI’s to answer the central question:

- Should we stay or should we go?

Additional questions include:

- Who are we, if not a waterfront community?

- Will things be better if we go? What new challenges will we face?

- If we go, what about those who’ve already left? Can they join the new community? Should they?

- Is this model replicable and scalable?

Takeaways

Most such presentations close with at least one each of a handful of technical solutions, pretty renderings of how fantastic a place will look in 40 years IF everything magically falls into place, or end in a shrug, as if to say “this problem is just too big.”

However, the lessons from “Designing Boston: Can We Talk About Climate Migration?” about engaging communities in dialogues were somewhat surprising, if not new, and broadly important for engaging in any discussion on the effects a changing climate will have to a community.

Rounded out by Darci Schofield’s examples of MAPC’s recent work with the Massachusetts coastal communities of Scituate, Duxbury, and Chelsea, all of which saw the effects of 2018 Nor’easters (Winter Storm Riley), these lessons include:

- Home, place, and community are central to identity.

- Understand emotional attachments before going into a community: listening, meaning, storytelling are key tools.

- Transferring of social networks from one place to another is challenging.

- Slow-onset effects (such as sea level rise) are often overlooked since there is no trigger point such as experienced with an acute disaster (such as an earthquake). However…

- Use time to our advantage.

- Don’t wait for federal of public money to materialize: empower local leaders to act now rather than react.

- ‘Retreat’ is a problematic term which comes with some baggage. Listen to communities, find, and use language that facilitates conversations rather than

Additional reading / listening

‘Retreat’ Is Not An Option As A California Beach Town Plans For Rising Seas, NPR, Dec. 4, 2018